The Buffalo Slave Case

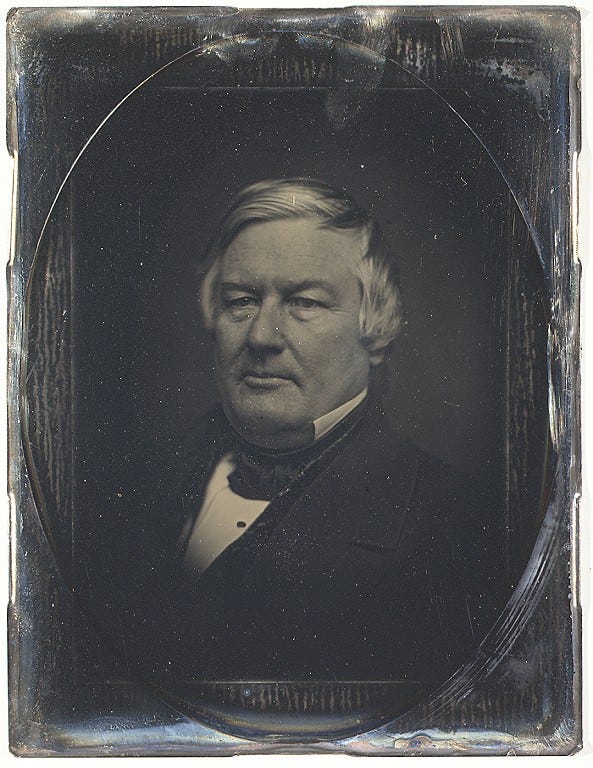

John Daniel Davis, Millard Fillmore, and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1851.

Wide River to Cross

On a dark October night, a Scotch boatman and a runaway stood in Black Rock Harbor and looked across the Niagara River. “You see those trees,” said the boatman, “they grow on free soil, and as soon as your feet touch that, you’re a mon.”

By morning, the Black Rock Ferry would carry Josiah Henson to freedom.

Henson wrote in his 1849 memoir, “When I got on the Canada side, on the morning of the 28th of October, 1830, my first impulse was to throw myself on the ground, and, giving way to the riotous exultation of my feelings, to execute sundry antics which excited the astonishment of those who were looking on…I was free.”

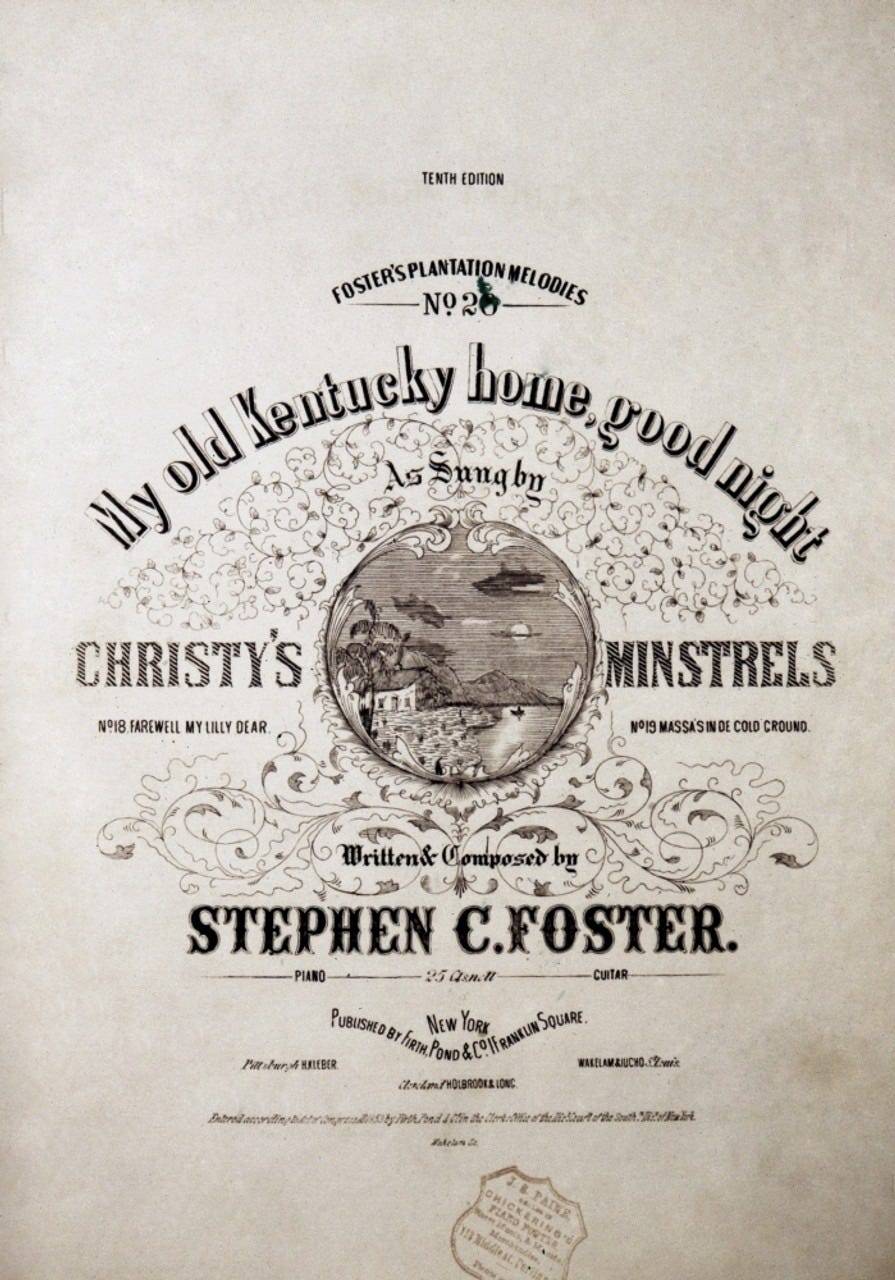

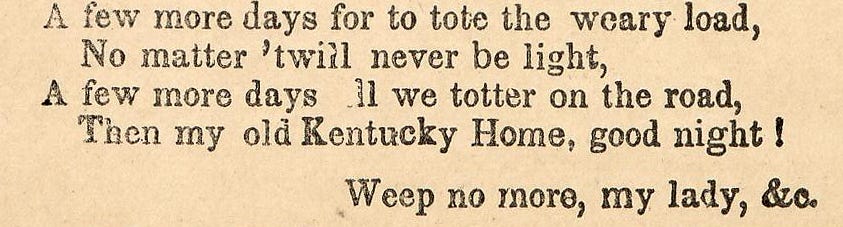

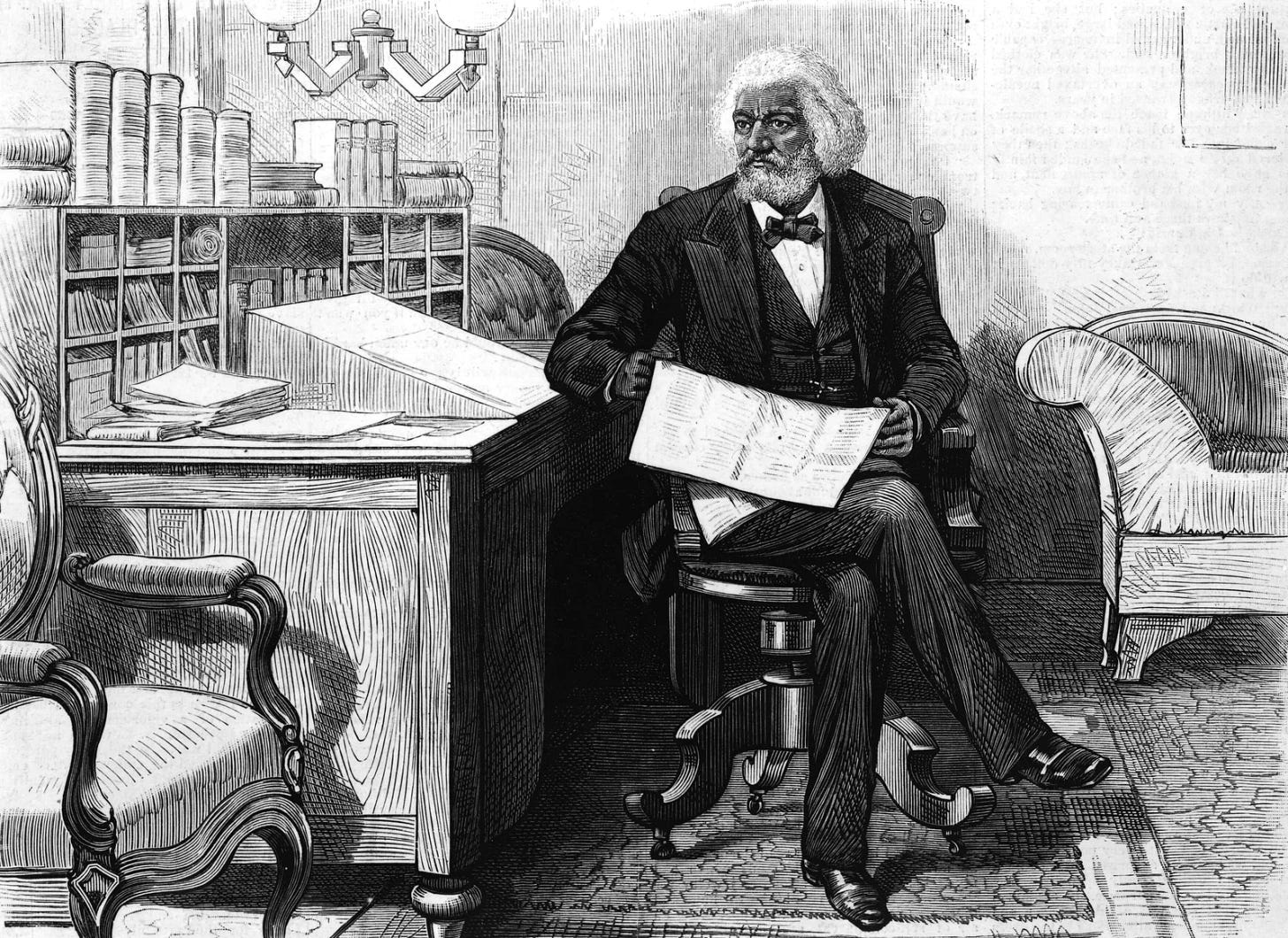

His story of enslavement and escape influenced Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1851 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which in turn moved Stephen Foster to pen the song “My Old Kentucky Home, Good Night” in 1852. Both were fictions of runaway slaves from Kentucky, like Henson, and both marked and influenced changing public opinion toward abolition. Though Frederick Douglass abhorred Foster’s minstrelsy, he praised this particular song for “awakening sympathies for the slave, in which anti-slavery principles take root, grow, and flourish.”

Somewhere on the road, blackface minstrel Ed Christy was singing the stolen song with his counterfeit complexion, as though the steward of both.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1851

Back in Buffalo, life and art were wheeling and turning about in a state of reciprocated imitation. In 1851, Millard Fillmore’s Fugitive Slave Acts pushed the cruel reality of slavery into the north. In August of that year, John “Daniel” Davis, runaway from Kentucky, brought the slavery debate to Fillmore’s hometown.

The Niagara had been one “wide river to cross” for decades. Canada’s abolition of slavery in 1830, in turn, made Buffalo a way station on the Underground Railroad. Though New York became a free state in 1827, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 mandated that runaway people in free states be returned to bondage. This therefore pushed enslaved people to escape into the sovereignty of Canada, just as Josiah Henson had.

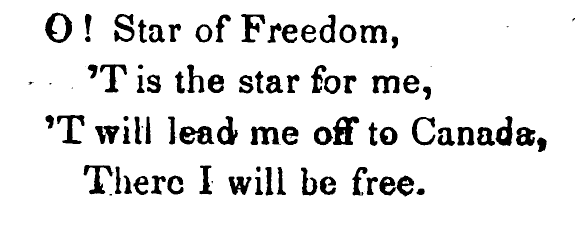

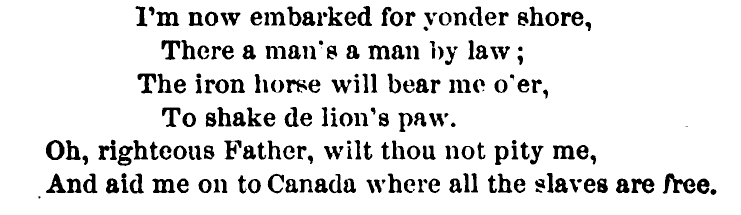

William Wells Brown escaped enslavement in Missouri and arrived in Buffalo in 1836, where he stayed and became a boatman helping others on to Canada, singing to the tune of Stephen Foster’s “Oh, Susanna”:

In 1856, Harriet Tubman led four people across the Niagara Suspension Bridge into Canada. As they crossed the line, they were all singing to the same Stephen Foster tune:

Northern states pushed back by passing their own laws requiring trials or banning use of local jails in fugitive slave cases. In 1842, Prigg v. Pennsylvania established that northern states were not obligated to aid in the search and arrest of escaped enslaved people. In return, southern slavers demanded stronger regulations.

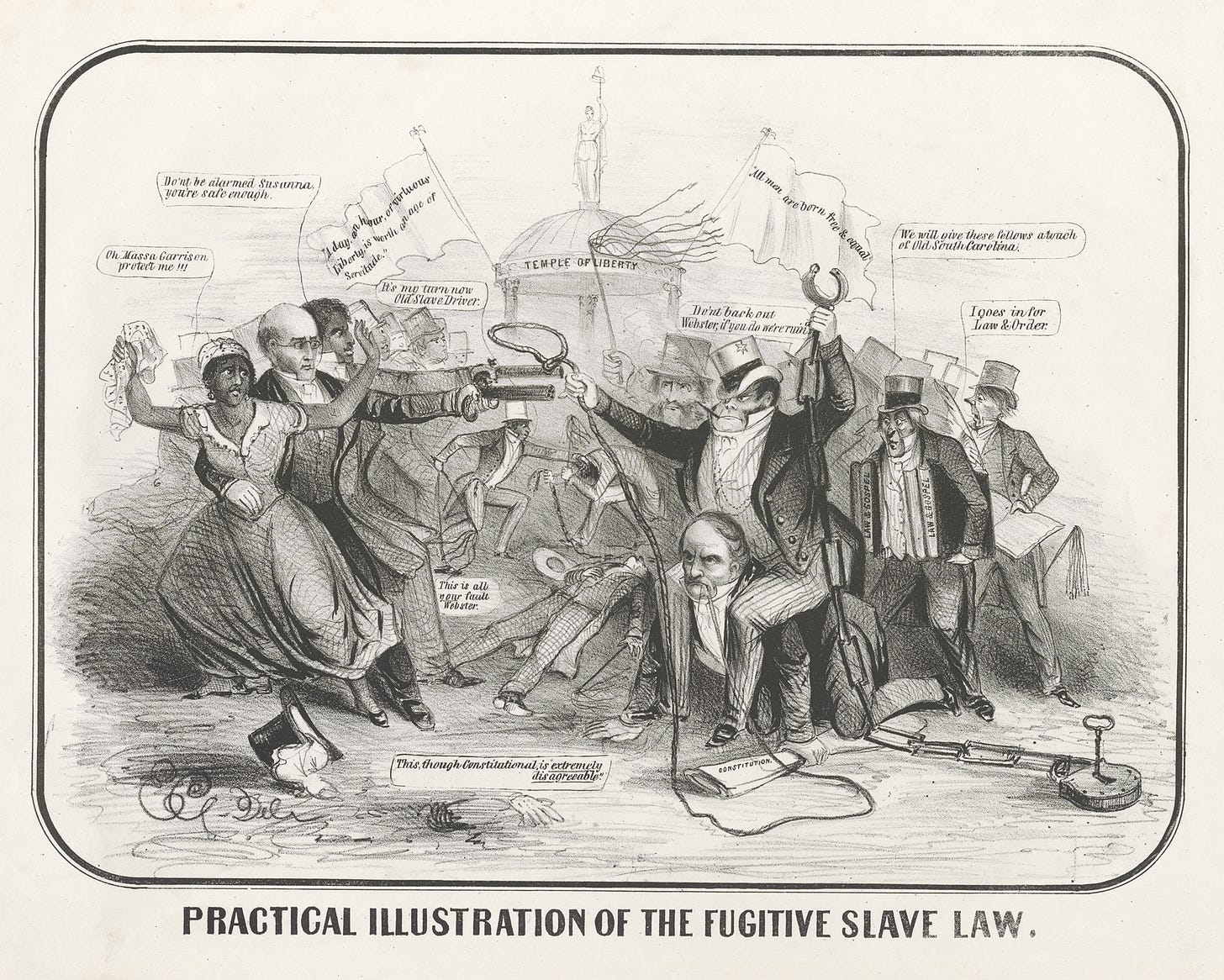

Thus, in 1850, former Buffalo lawyer and accidental president, Millard Fillmore, passed a new fugitive slave bill into law. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 imposed thousand dollar fines on officials who refused to comply. For citizens who aided fugitives, the same fee came with a six month sentence. The “Bloodhound Law,” as abolitionists nicknamed it, authorized agents from the south to hunt runaways through the north, and trials were done away with, thereby permitting slave hunters to act as kidnappers, apprehending free people unattested and selling them into slavery. Previously, an enslaved person became enfranchised upon entering a free state. The new law put an end to this precedent.

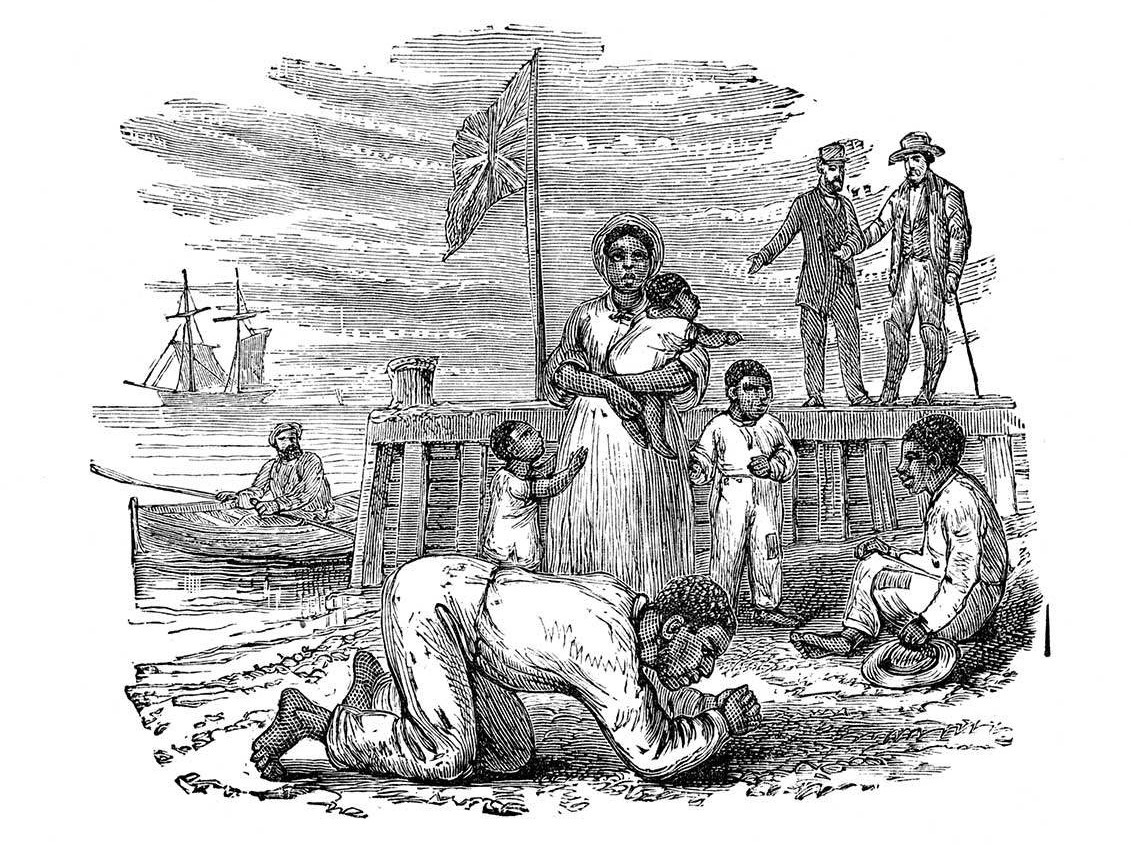

The consequences were disastrous. The new Fugitive Slave Act made de facto slavery legal in free states. African Americans who had lived freely in the north were now impelled to leave for Canada to avoid kidnapping. The African Canadian population increased by 20,000 over the following decade. William Wells Brown was lecturing in England when the law passed. He stayed exiled in Europe until he could buy his freedom in the United States in 1854. Despite the tightening of the law, Underground Railroad activity continued.

The country was polarized on the issue and the Fugitive Slave Act only furthered this divide as the country neared civil war.

In Buffalo, pastor John C. Lord devoted a sermon to “The Higher Law in its application to the Fugitive Slave Bill.” He turned his congregation to Colossians 4:9 for justification. “Paul sent Onesimus back to his master, on the very principles which he enjoined upon the Romans — subjection to existing civil authority.”

Lord preached, “I would beseech them to stand by the Union, to obey the laws, to frown upon agitation in this crisis of our beloved country.”

The Buffalo Daily Republic asserted, “‘Agitation,’ thanks to the patriotic and humane feelings of northern people, will not be ‘silenced’ until this infamous law is blotted from the statute book of the nation.”

Buffalo was clearly divided by the Fugitive Slave Act. The Act challenged whether the people of Buffalo would uphold the law of Buffalo’s most revered citizen, President Millard Fillmore, or continue to aid fugitives as they had for decades. This division would be tested in full in the summer of 1851.

Daniel in the Lion’s Den

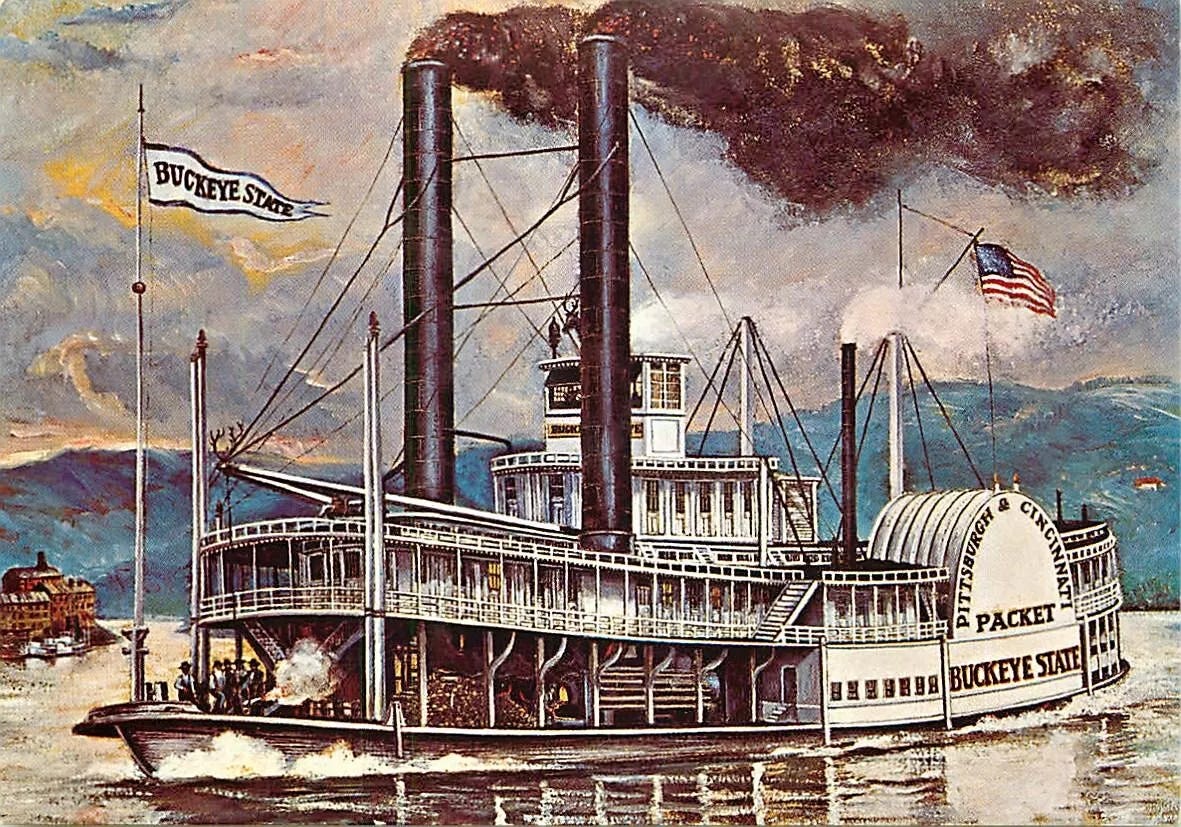

On August 15, 1851, a steamboat called the Buckeye State arrived in Buffalo carrying 66 bales of wool and one John “Daniel” Davis, a 24 year old fugitive working as the ship’s second cook. Around noon, Davis and the rest of the galley crew were dishing dinner when Buffalo police officer J.K. Tyler and Deputy Marshal George Gates arrived on the scene. “It was so dark [in the galley],” Gates said, “that it was difficult to discern anything very distinctly.”

Arriving just behind the law enforcers was head cook Robert Jones. Marshall Gates told Jones he had a warrant for one of his men. Jones replied that he wanted “to get up my dinner” as he passed into the galley.

Meanwhile, on the deck above the galley hatch was Benjamin Rust. Rust, described as a “tall man but otherwise a small man,” was a slave catcher from Louisville operating as an agent for banker George J. Moore, who allegedly owned second cook Davis. As the porter set the table in another room, he saw that Rust went “to a wood box and picked up a stick of wood and hefted it in his hand and then threw it back and picked up a larger one.”

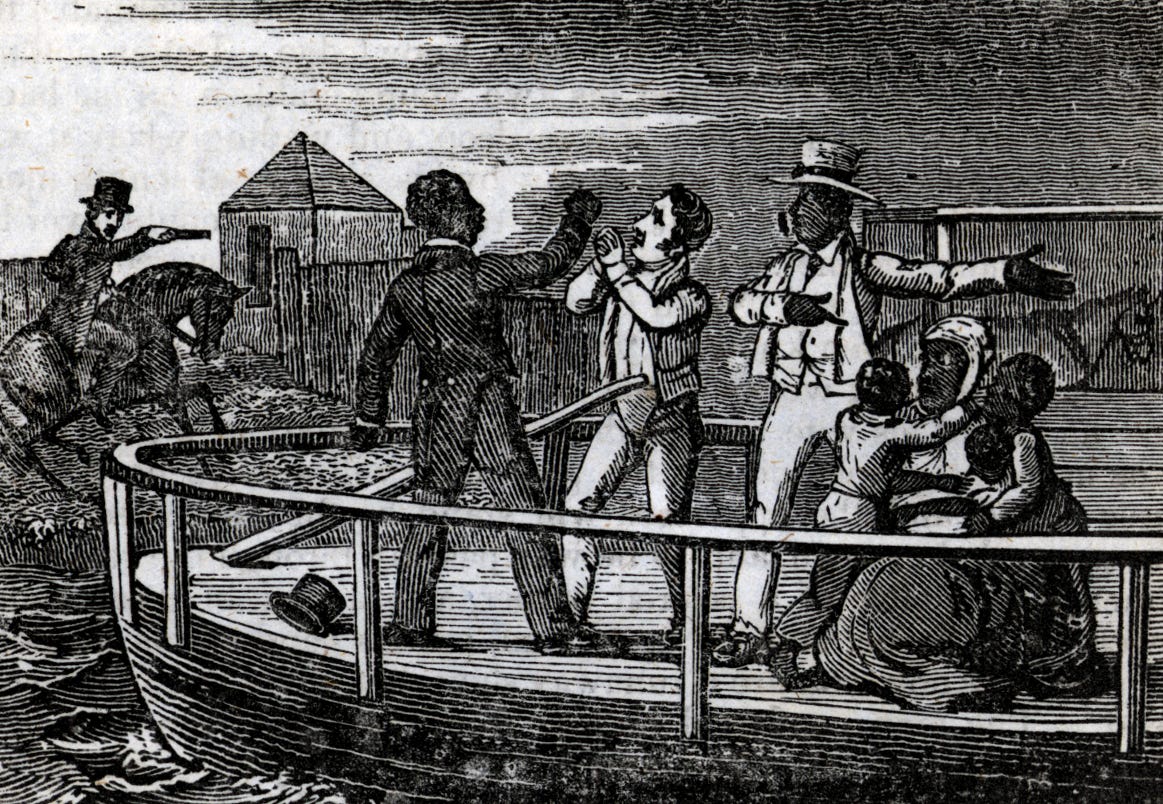

Down in the galley, Gates demanded again that he have the fugitive man. The Buffalo Commercial Advertiser reported that Davis “refused to accompany the officer, and, with his four companions, laid hold of their knives as if determined to show fight, and threatened to ‘walk over corpses’.” When told they were surrounded, “Daniel dropped his knife and darted up the small hatch ladder to make his escape.”

By now, Rust was kneeling over the hatch holding the billet of wood in both of his hands. Deckhand Barney Corn said,

“Daniel came up thro’ the hatchway; saw his head appear above the deck; he had got his head only up when [Rust] raised his stick in both hands [above his head] and struck him with all his force. When the blow was struck I saw Daniel fall -- I thought at the time Daniel was dead.”

Davis fell back into the kitchen and was burned on a stove. The blow to his head was so violent, numerous crew members thought he was dead. Jones pulled Davis away from the stove and headed up the hatch fast enough to follow Rust as he ran off through the nearby Bemis Brother’s grocery and out a door onto Water Street. Someone yelled, “arrest that man,” and the Buckeye’s wheelman John Watts caught up with Rust and brought him back to the boat. Both Davis and Rust were carried across the Commercial Street Bridge over the canal and up a block to the commissioner’s office in Spaulding’s Exchange.

The Buffalo Daily Republic reported, “An immense and excited crowd had gathered round the doors of the Exchange and, upon the appearance of the wounded and manacled negro, the feelings of the people could be no longer restrained, and a rush was made towards the officers who [led] him in charge and the slave-catcher who followed closely upon the track of his prey.”

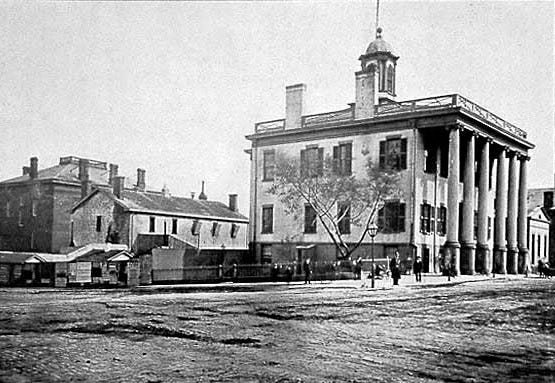

“It was only by the greatest exertion that the officers were enabled to reach the carriage,” as they tried to make it to the courthouse in Lafayette Square. The crowd blocked the carriage until Sheriff Farnham, “considered it necessary to make a liberal show of pistols, which were presented at the breasts of those who approached the carriage and had the effect of driving them back.”

Rust and Davis were held in the old stone jail. Davis “was thrust into one of the closest, darkest, lower cells, with prison bracelets on his wrists...at the same time, Mr. Benjamin Rust, the ‘gentleman from the south,’ charged with committing a felony, was locked up in the same jail. He was politely conducted by the Sheriff and Jailor into an upper apartment of the Stone House set apart for debtors and lady boarders,” as reported by the Buffalo Republic. A large crowd remained outside the jail to ensure Davis’s safety.

The next day, “The Hon. H.K. Smith, commissioner for carrying into effect the provisions of the Fugitive Slave Law, took his seat upon the bench and the examination commenced.” Here Davis’s escape was recounted.

George J. Moore of Louisville, Kentucky purchased Davis from a man whose name may have been Fraser for $700 sometime around 1850. Moore hired Davis out to cook on a steamboat, the Anna Lennington, and it was in that position he made his escape in August of 1850, possibly in Cincinnati in the free state of Ohio. From there, Davis went to Cleveland where he worked at the Durham House until he landed a job as second cook on the Buckeye State. He had only made two trips on that boat before finding himself in the courtroom.

Davis’s defense argued that the act of taking Davis into a free state enfranchised him, a precedent that was well set.

Commissioner Smith denied this defense based on Section 10 of the Fugitive Slave Act, ruling that Rust was authorized to take Davis back to his master, but not until word was sent to Moore to ascertain if he were willing to sell, and the citizens of Buffalo willing to buy, Davis’s freedom. Otherwise, “That slave shall go back to Kentucky to his master, according to my decision, and if anyone dare oppose that decision, he shall be shot down,” Smith closed the hearing.

On August 16, the Buffalo Courier reported, “All good citizens must unite in congratulations that the question has been decided, if there were room for question, that the citizens of Buffalo are in favor of Law and Order.”

That same day, The People vs. Benjamin S. Rust began. Over two days, the District Attorney brought charges of brutal assault and battery with intent to kill, to which Rust pleaded not guilty.

The idea that Davis had a knife and Rust acted with necessary force was quickly done away with. Marshall Gates testified that, “Daniel had something in his hand; does not know what it was. The room was dark.” Under examination, the cook, Robert Jones, stated that, “Daniel had a spoon in his hand,” and, furthermore, Jones ordered Davis to go up on deck, “that they might see if he was the man.” Davis complied and went up the ladder. Jones clarified that the other direction where Gates and Tyler stood led “to the cabin -- a way we never went,” adding, “there is no way of going up for the cooks but that.”

After thorough testimony that there was no knife and no attempt to escape, Rust's actions were ruled “common assault” and he was fined $50 in damages. A travesty considering anyone else would have been sent to the workhouse for hard labor and the paltry sum of $50 would pass through Davis’s hands and into that of his enslaver.

On August 19, the Buffalo Daily Republic printed 21 legal precedents reinforcing that Davis was enfranchised by his presence in a free state. Alongside these columns is the report that Rust received word from Moore that he would sell Davis for no less than $1000, for which local citizens took up collection and waited for Smith's decision to be reviewed by District Court Judge Alfred J. Conkling.

One Bob Markle wrote a letter to Frederick Douglass in Rochester on August 20 reporting what he had witnessed in Buffalo two days after Davis’s assault. “I do not believe Daniel will be taken back to slavery. If he can be re-enslaved after having been made free by his master’s permitting him to come into a free state, then a man born free, or a man emancipated, or a man bought, can be re-enslaved.”

The next day the Frederick Douglass Paper published an article on the case concluding, “To the men of color who would say be prepared for the worst. You are every one, (as we are), liable to be pounced upon at any moment, and snatched away from all you hold dear on earth.”

On the morning of August 29, the Buffalo Courier printed a letter allegedly written by Davis addressing the “Colored Population of Buffalo” thanking them for their help, but imploring them to do no more. “We colored people of Kentucky are about as well off as you are. I am going back,” the purported letter stated, in apparent longing for that old Kentucky home far away. Within that day and the days that followed, the letter’s authenticity was torn apart in both local and national papers, condemning it as plagiarism from the “law and order” crowd and friends of Millard Fillmore.

Not all citizens were in favor of “law and order” and the southern appeasement it was married to. An unnamed writer submitted the following song to the Buffalo Morning Express in the first week of September, criticizing the Buffalo episode and asking “where’s the law that proves us [or anyone] free?” The song is titled “The Buffalo Slave Case: A Song for the Serviles and Lower Law Doctors.”

On the morning of Saturday August 30, Marshall Gates led John “Daniel” Davis into the courtroom where Judge Conkling sat on the bench. “Daniel looked full of hope and when some of his colored brethren shook him by the hand and told him he was certain to recover his liberty, his eye brightened.” After review of the case Judge Conkling issued a writ of habeas corpus, freeing Davis.

“The decision was based on the ground that the Fugitive Slave Law, or that clause of it under which the man was claimed as a fugitive, is prospective and not retrospective in its operation; and as the escape of Daniel was alleged to have been made previous to the passage of the act, it could not apply to his case.” If Davis had escaped after September 18, 1850, he would have been returned to slavery.

“Daniel, hurrying from their vicinity, stepped into a carriage and made tracks for the British possessions,” the Republic reported. “Indeed, many thought that he was in a great hurry, for the horses attached to the carriage which conveyed him to the Niagara River, where a boat was in waiting to carry him across, were put under a full run the moment they left the Court House and never slacked their pace until they reached the river.”

A headline from the New York Daily Tribune exclaimed, “Daniel in the Den and Out.” Another paper noted the sad irony in Davis finding under a monarchy the liberty which was denied him in a republic.

Daniel went from the lion’s den and across the river to shake the lion’s paw, just like Josiah Henson and many in between. “Didn’t my Lord deliver Daniel,” the old song asks, “then why not every man?”

edited by Sally Schaefer